The Sky Is Falling! Responding Rationally to Headline Vulnerabilities

It’s happening more and more.

High profile vulnerabilities like Meltdown and Spectre are disclosed, and become headline-grabbing news not just in the technology press, but on general news outlets worldwide.

Even if the vulnerabilities aren’t associated with an attack, the news reports rattle C-level executives, who ask the security team for a plan to address the by now notorious bug, and pronto.

Often, a counter-productive disruption of the normal vulnerability and patch management operations ensues, as those involved scramble to draft a response against the clock in a panic atmosphere, punctuated by confusion and finger-pointing.

“Should I just immediately be jumping and reacting? Should I start deploying patches, and then go from there? I’m going to argue that that’s not always the case,” Gill Langston, a Product Management Director at Qualys, said Wednesday during a presentation at RSA Conference 2018.

The right approach

What security teams should aim for is a coherent, appropriate and rational response plan that is grounded in a factual and comprehensive assessment of the situation, said Langston, whose presentation was titled “The Sky Is Falling! Responding Rationally to Headline Vulnerabilities.”

“How can I put this together and send something back to the C-level executives that says: ‘This is my recommendation for now.’ It may not always be to go deploy the patches,” Langston said. “Create a plan, and then react, review and improve it over time.”

A key step in dealing effectively with this type of “news event” vulnerabilities is to have a proper and solid vulnerability management and remediation program in place. That way, organizations are in a better position to do a precise risk assessment of disclosed bugs on a continuous basis, according to Langston.

This also means that when a high profile vulnerability is announced, security teams have a head start. That way, they don’t have to go back to square one to ensure they are in fact identifying all assets before they can start to react.

Organizations will be able to pick the most appropriate course of action, which depending on the case, can be to patch right away, to mitigate when remediation is complex, or to monitor and wait before acting.

Below are three recent examples of each scenario.

Patch now, unless you “wanna cry” later

Most organizations should have prioritized patching the vulnerability that was exploited by the WannaCry ransomware, way before the attack was unleashed, according to Langston. Instead, the WannaCry attack infected 300,000-plus systems and disrupted critical operations globally.

Microsoft disclosed the Windows vulnerability (MS17-010) in mid-March 2017 and made a patch available. At the time, Microsoft rated the vulnerability as “Critical” due to the potential for attackers to execute remote code in affected systems.

The vulnerability also had a number of other red flags that made it stand out as a particularly concerning one. In mid-April, the vulnerability became even more dangerous when the Shadow Brokers hacker group released an exploit for it called EternalBlue.

So organizations had a window of about two months to install the patch before WannaCry was unleashed in mid-May. Had most affected systems been patched, WannaCry’s impact would have been minor.

“In most cases, organizations that follow the standard patching cycle of 30 days, they were already protected. And two months in, you got a second shot at it,” he said.

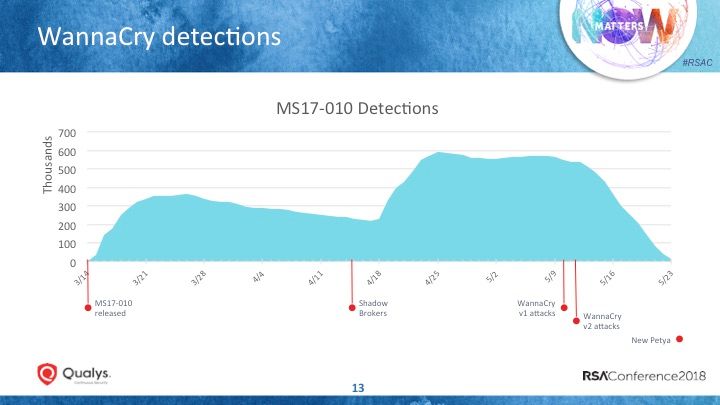

Langston displayed a graph with Qualys vulnerability scanning data showing that between mid-March and mid-April, detection of affected devices spiked and gradually declined as organizations scanned and patched their systems.

However, the number of vulnerable systems shoots up after the EternalBlue release, after organizations apparently expanded the initial scope of scanned IT assets.

And there’s an important lesson here. “When you’re dealing with a vulnerability that can jump around your network, if you’re not identifying all of the assets, you’re already behind the eight ball,” he said.

The graph shows that widespread patching didn’t fully kick in until after the WannaCry attacks began.

Fom WannaCry, Langston identified some key no-nos: A slow identification of all at-risk assets; a tendency by IT operations teams to treat all issues with similar urgency; and a complacency among end users to delay rebooting their machines to finish the patching process.

Strut your firewall

Langston then discussed the Struts web application vulnerability that was exploited most famously at Equifax, leading to that consumer credit reporting agency’s massive data breach. On the same day that Struts was disclosed, and a patch made available, an exploit was also released, so the risk was high.

Because web application vulnerabilities tend to be difficult to remediate, often requiring a rebuild and long testing cycles, Struts highlights the importance of mitigation. In this case, a good plan would have been to use a web application firewall, while patching was in progress, he said.

Meltdown and Spectre: All bark and no bite?

Then there are the Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities, which caused widespread alarm upon their disclosure in early January of this year, but for which there are only ineffective proof-of-concept exploits so far.

In the panic that was created, vendors such as Microsoft and Intel released faulty patches that IT departments rushed to apply, only to have to react after they caused system problems, including data corruption and performance issues.

Qualys data of vulnerability scans for Meltdown shows an initial push to install OS patches, followed by a long plateau of inactivity, as organizations probably weighed the fact that there were no exploits, and that the patches were problematic.

A big lesson from Meltdown and Spectre? “Just because it’s in the news doesn’t mean it’s an emergency,” Langston said. In other words, it’s an example of a scenario where the most prudent thing to do is to monitor the situation and wait, instead of rushing to patch.

Best practices

Langston recommends these six tips for crafting the best response to a notoriously public vulnerability:

- Identify high-risk vulnerabilities often

- Track the specific risk to your organization

- Determine the best course of action

- Decide when to communicate with internal stakeholders

- Update regularly

- Work the plan and improve it

It’s also key to get buy-in from all the teams that will be involved in drafting, approving and executing the plan, including executives, security operations, DevOps, and IT operations. “Build the playbook together,” he said.

The response plan should have four main elements:

- Preparation, which involves ensuring that all assets are identified, that the triggers are documented and that the communication outreach is built

- Reaction, which involves working the playbook, deciding on the course of action (fix, wait or mitigate), and communicating with your users

- Revision, which involves reviewing the outcomes of the executed plan, and identifying improvement areas

- Improvement, which involves collaboration to refine the response, modifying the plan based on findings, and extending the plan to all high-severity vulnerabilities

This should all amount to a rational, measured response, instead of to a knee-jerk reaction that leads to erratic, misguided decisions and actions.

“If you don’t have some response plan, you end up bouncing off of each other, pointing fingers and slowing down the entire process,” he said.

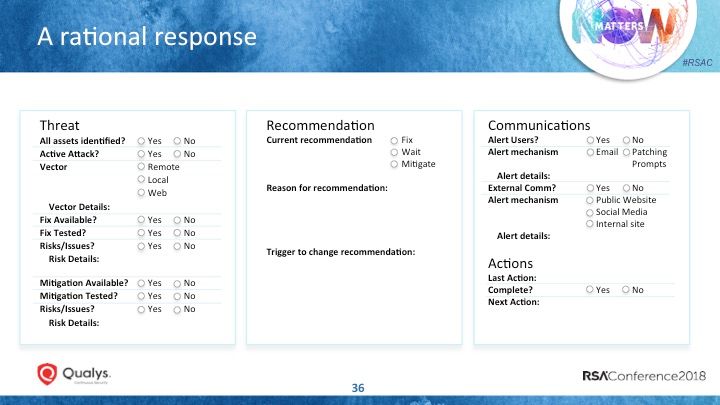

Below is a checklist template that Langston suggests could be helpful in analyzing how to best respond to a “headline vulnerability”.

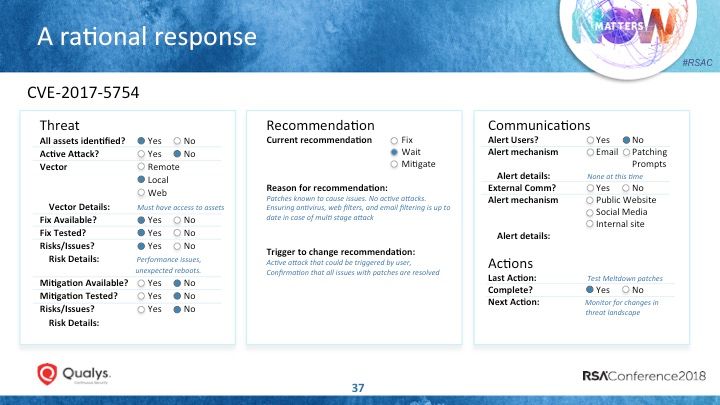

Here’s how that checklist might look when filled out by a hypothetical organization for the Meltdown vulnerability.

This information can also be enriched and expanded using automated dashboards with threat feeds and other resources that are updated in real time and that allow security teams to do in depth analysis of relevant data.

The goal is that in the face of a headline-blaring vulnerability, organizations can come up with a well thought and sensible plan. “A methodical approach leads to a rational response,” Langston said.